Trust is very important in our lives. As children we put our trust in our parents. As we grew we learned to make decisions regarding when we should trust and when we should be more circumspect. When we start a new job or project we spend time figuring out who we can turn to for advice, who we can trust, and whose advice we need to double-check.

With the rise of the networked society and the increasing use of social networking tools, trust is probably on our minds every day. Who doesn’t hesitate before clicking on that shortened URL from a friend on Facebook or someone we follow on Twitter and wonder whether it’s genuine or whether the account has been hijacked and the link is about to initiate some malware infection from an unknown server in some unknown location that just may not be caught by our spam/malware protection software?

So, trust is probably at the forefront of our thinking most days.

Trust and Getting Things Done in Organisations

Trust relationships are powerful allies in getting things done in organisations. I think we’re all aware of that.

If we’re working in L&D strong trust relationships with senior leaders and middle managers are vital. Without a high level of trust anyL&D manager will find it almost impossible to embed a culture of learning in their organisation.

Trust and ‘A Seat at the Table’

Like HR, many training and learning departments have been trying for years to gain a seat at the top table in their organisation. To a large extent these attempts have failed and it’s worth asking why this is the case.

Although the age-old management credo that ‘our people are our greatest asset’ has now moved beyond lip-service in many organisations (despite the fact that the value of this ‘greatest asset’ still isn’t explicitly shown on a balance sheet), the leadership of the part of the organisation that’s directly responsible for working, advising and helping extract maximum performance from this asset is still not welcome as an equal member of the senior management team. Sure, CLOs and senior L&D managers may regularly be invited to present new initiatives or ‘state of play’ reports to senior management meetings, but that’s different from being inside the tent or having a ‘seat at the table’ and contributing to ongoing strategy development.

This situation raises a couple of questions for me – and they’re both tied to trust and trust relationships.

The first question is: “Do most senior managers actually believe that L&D managers play an important role in keeping the organisation running and on-track’’?

Associated with this is a second question: “Do most managers think that L&D can add value”?

I think both of these questions come back to competence trust and to relevance. They beg the question as to whether business managers have confidence that their L&D department can make a difference, impact organisational performance and the balance sheet. In other words, is L&D relevant in business terms? If it isn’t, then why include passengers on the senior leadership team.

So, what can CLOs and L&D managers do to address this?

Different Types of Trust

Firstly it’s worth understanding about the some of the different types of trust and then developing a plan to build trust with your senior business colleagues.

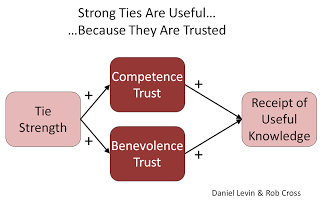

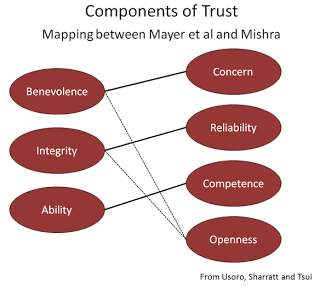

Trust is qualified in a number of ways. For some there are two types – competence trust and benevolent trust. The difference is this. The first is the ‘I believe you know what you’re talking about, so I’ll trust your opinion’ type of trust. In other words,’ I believe that you’re competent so I’ll trust you’. The second is the ‘I believe that you won’t tell me anything that will harm me, so I’ll trust your opinion’ type of trust.

Another view of how we come to trust someone or not is defined as being based on our assessment of their benevolence, integrity and ability.

Now, no matter how we define it, it’s important that L&D managers address trust in its many forms in building solid relationships with senior business managers. And trust is a two-way thing. I’ll trust you if you trust me…

Moving L&D up the Agenda

If you want to move L&D up the agenda and have the opportunity to be involved in strategic decision-making, you need to demonstrate that the L&D managers and their teams are trustworthy.

You do this by building trust relationships. By demonstrating that you understand the problems business managers are facing, and then by working with them to deliver solutions to resolve those problems demonstrably, quickly, efficiently. By doing this you will start to build competence trust and benevolent trust relationships. You’ll also go a long way towards engendering your managers’ trust in your ability and competence to deliver business solutions, and a feeling that you are a trusted partner, someone who can be relied on.

If you work on this basis – get close to your business managers, analyse their problems with them, advise them of the options open to them from your professional L&D standpoint, take their input, and then develop effective solutions, and demonstrate the efficacy and impact in the most straightforward way possible – in business terms – you will find that a trust relationship will develop.

That’s the way to get a seat at the top table. It’s not magic. You’ll just find yourself being invited to provide advice and suggestions at early stages in the strategy-setting process. You’ll find people calling you up because the CEO or CFO has recommended you as someone who can help managers with their problems.

You may even find HR colleagues asking how you have managed to become a trusted consultant and advisor to the CEO and CFO and other senior leaders.

ConsultMember of the Internet Time Alliance and Co-founder of the 70:20:10 Institute, Charles Jennings is a leading thinker and practitioner in learning, development and performance.

ConsultMember of the Internet Time Alliance and Co-founder of the 70:20:10 Institute, Charles Jennings is a leading thinker and practitioner in learning, development and performance.

Do most managers think that L&D can add value?

Do you have examples of organisations where this is really true? Military maybe?

I've worked with a number of managers who believed that L&D adds value, Chris.

With some it is clearly a belief rather than a reasoned decision taken on the basis of evidence. However, others have come to the view that L&D has added value based on demonstrable impact on their business results – using customer satisfaction indicators, reduction in error/re-work rates etc. Certainly a number of the managers I worked with at Reuters were in the latter category.