A Revolution or a Slow Demise?

I’ve recently read Clark Quinn’s excellent new ‘Revolutionize Learning & Development’ book. Clark always provides a thoughtful and enlightening perspective. There are some observations and suggestions in here that get to the heart of the issues around the fact that our approaches to building capability through learning need a radical rethink.

I’ve recently read Clark Quinn’s excellent new ‘Revolutionize Learning & Development’ book. Clark always provides a thoughtful and enlightening perspective. There are some observations and suggestions in here that get to the heart of the issues around the fact that our approaches to building capability through learning need a radical rethink.

Despite the book’s title (or maybe that’s the point of it) Clark’s focus is not so much on learning and development as on performance. It’s about the output rather than process. Learning as simply a means to improve performance.

I agree totally with this approach.

Learning itself may be a noble aim but it’s not an end in itself in the context of work. Professionals in any field are usually recognised (and paid) for results. Whether you’re working in an HR or L&D department, or for a commercial company providing learning tools and services, or for a college, university or business school, results matter. It’s no different from any other profession. Lack of demonstrable results lead to consequences such as limiting of funding, closure or contract cancellation.

We know that the results of learning and development activities can only be determined by changes in behaviour (after all, at its heart that’s what ‘real learning’ is) and behaviour change needs to be measured in terms of what individuals, teams and organisations can do and are doing, that they couldn’t do previously, or what they’re doing better than before. ‘Knowing’ does not prove ‘learning’.

This point seems still to be lost on many HR and learning professionals.

Quinn suggests that a focus on performance augmentation should be at the core of all learning and development activity. He describes a range of methods to achieve the transformation from learning to performance. This book is very helpful in that way and builds on the work of others such as Gloria Gery, Mary Broad and Harold Stolovitch.

If learning professionals and learning departments don’t adapt and change, Quinn argues, they will be revealed not simply as having no clothes, but as being so out of step that they will wither and die, or be removed from the value chain.

The evidence seems to strongly support Quinn’s arguments.

One piece of aligning data comes from the Corporate Executive Board’s 2012 study ‘Building High Performance Capability for the New Work Environment’. This study sampled 35,000 managers and employees across the globe. Part of its focus was examining the links between stakeholder expectations, current practices and results delivered by L&D, and steps toward adapting to the needs of the ‘new work environment’.

Characteristics of this new work environment include:

-

increased demands on the amount of work done with co-workers in different locations

-

increased numbers of individuals involved in making decisions

-

increased need to navigate complex work processes

-

increased requirement for employees to use analytical competencies to process data and make decisions

-

increased importance of ‘network performance’ over individual task performance

-

increase in need for ‘network performance’ capabilities such as:

-

teamwork

-

self- and organisational awareness

-

process design

-

creativity

-

systems thinking

-

The startling findings of this CEB study were that in order to achieve breakthrough employee performance and achieve their short-term business goals (goals for the next 12 months) stakeholders reported they required an average improvement of around 20-25%.

Business leaders stated they required a 20% improvement in employee performance to achieve their goals, managers needed to see the performance of their teams rise by 22%, and HR leaders believed that their workforces needed to improve by 25% to achieve business goals.

At the same time the study found that simply improving existing practices in the delivery of classroom training will yield only limited gains.

The major reason for this is that by-and-large classroom training techniques have become more efficient over the years (we’ve been at it for a long time) and only marginal further improvements are possible.

Fig: From Corporate Executive Board’s ‘Building High Performance Capability for the New Work Environment’ study, October 2012.

Fig: From Corporate Executive Board’s ‘Building High Performance Capability for the New Work Environment’ study, October 2012. Data from CLC Learning and Development High Performance Survey: CLC Training Effectiveness Dashboard. Used with permission.

The simple conclusion CEB draws from this study is that ‘current course and speed won’t get us there’.

However there’s a sting in the tail, too. An earlier piece of Corporate Leadership Council research, L&D Team Capabilities Survey (2011), found that although participants and their managers report high levels of satisfaction on individual learning interventions, their feedback on the performance of the L&D function as a whole was extremely low.

-

“Only 23% of line leaders report satisfaction with the overall effectiveness of the L&D function”

-

“Only 15% of line leaders report the L&D function is effective in influencing their talent strategy”

-

“Only 14% or line leaders would recommend working with L&D to a colleague”

Clearly there is a huge gap between what stakeholders need from their L&D departments and what is currently being delivered.

The imperative is clear, but are L&D leaders and professionals stepping up to address it?

Clark Quinn and I would both argue that there is some good practice and some emerging practice being demonstrated which can close these gaps and transform the learning function into an effective organisational lever. But we need wider fundamental changes if we’re to do so at speed and scale.

So, what are these fundamental changes?

Fundamental Change for L&D – Learning Lessons from Our Changing Concept and Use of Time

I believe we can learn some lessons of where we are and where we need to be as HR and L&D professionals, or as anyone who has responsibility for workforce development and performance, by looking back at how we have adapted our ideas and practices around the concept of time.

It might seem a strange analogy but I think it fits well to the current challenge.

Measuring Time by Observation For millennia people measured time based on the position of the sun. When the sun was directly overhead it was noon. That was the only way to know and that was the way time was calculated. The concept of hours and minutes wasn’t needed or used.

This was a bit like the one-trick classroom pony that has been used for many years. Training was seen as the only solution to performance problems. If training didn’t work, then we trained them again – and again.

Sundials and Water Clocks As technologies such as sundials and water clocks evolved to allow us to measure time more accurately and efficiently we adopted them.

Sundials and Water Clocks As technologies such as sundials and water clocks evolved to allow us to measure time more accurately and efficiently we adopted them.

This was little like the uptake of online courses and eLearning. We found that we could reach more people using fewer resources, faster. However, we were still using the same mindset and thinking of solutions as being ‘courses and programmes’. Learning by physically or mentally taking people away from the workplace.

Mechanical Clocks By the Middle Ages sundials and other approaches based on natural ‘tools’ had been replaced by the the mechanical clock. Each city had its mechanical clock which was set by the angle of the sun at noon. However every city had its own, unique time zone.

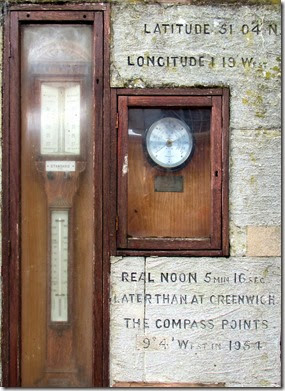

The photograph above is of the instrumentation on an external wall of the Guildhall in Winchester, the city where I live. Winchester is one degree 19 minutes west of Greenwich, the point designated as ‘absolute zero’ in terms of longitude. One degree 19 minutes at 15 degrees North computes to roughly 86 miles. So the ‘real time’ at Winchester is 5 minutes 16 seconds behind the time at Greenwich. About 60 miles further west the people of Bristol worked to a time that was a further few minutes later than Winchester.

This situation was a bit like the the industry that has arisen over the past 20 years with multiple LMSs and content creation tools and other learning offerings. We were tied into many bespoke systems – there were some standards and reference models to make things slightly easier, but our efforts were were still stuck on point-solutions. We produced smarter modules and courses, better learning pathways, or integrated new technologies but the overall outcome was to make the learning landscape more complex and full of ‘busy work’.

The Disruptive Driver The most significant disruption to our concept of time came not through new time-keeping inventions but through a totally different invention in a totally different domain – the railway network.

In 1840 the Great Western Railway in England (running from London to Bristol and further west into Devon and Cornwall) applied a standard railway time across its network, based on London Time (or Greenwich Mean Time).

“The key purpose behind introducing railway time was twofold: to overcome the confusion caused by having non-uniform local times in each town and station stop along the expanding railway network and to reduce the incidence of accidents and near misses, which were becoming more frequent as the number of train journeys increased.The railway companies sometimes faced concerted resistance from local people who refused to adjust their public clocks to bring them into line with London Time. As a consequence two different times would be displayed in the town and in use, with the station clocks and (time) published in train timetables differing by several minutes from that on other clocks. Despite this early reluctance, railway time rapidly became adopted as the default time across the whole of Great Britain, although it took until 1880 for the government to legislate on the establishment of a single Standard Time and a single time zone for the country”. (Wikipedia ‘Railway Time’)

There was undoubtedly opposition to this new disruptive approach to an age old issue. Charles Dickens was one who expressed concerns. In Dombey and Son he wrote “There was even railway time observed in clocks, as if the sun itself had given in.” However, despite concerns and opposition, railway time was rapidly adopted across the world. A train crash in New England in the USA in 1853 caused by the guards having different times on their watches was just one of many accidents and mishaps that made it obvious that a new order was needed.

L&D Disruptions

Our approaches to learning are being confronted by not just one external disruptive driver, but by many.

-

Change is occurring at an increasingly rapid rate. Taking people away from the workplace to train them in order to keep up and do their jobs better is becoming a less viable option by the day.

-

Increasing complexity and reliance on tacit knowledge means that ‘extracting’ knowledge and codifying it into modules and courses is not only becoming more difficult, but often slows speed to capability.

-

Daily pressures make it less-and-less likely that people can take time away from their work to attend a course. Although it is important to have time for reflective practice and sharing with others most structured training and development courses are built around content, not conversations, sharing and reflection.

-

Evidence suggests that most mistakes are due to errors of ineptitude (mistakes we make because we don’t make proper use of what we know) rather than errors of ignorance (mistakes we make because we don’t know enough). Yet most approaches to learning assume the opposite is the case.

-

The rise and rise of social medial and technologies has opened up opportunities for people to access help and support from across wider networks in almost real-time. We don’t need to ‘know’ the minutiae if we know where to find it, or who can help us. This challenges many assumptions of our current learning approaches.

There are many other disruptors confronting existing models and practices used by L&D departments and their learning providers. The point is, like the impact of the railway on timekeeping there is an urgent need to adapt. The old must give way to the new. Carrying on regardless is not an option. But many are still doing just that, or focusing on incremental changes only. But everything has changed, and no change in response is simply not an option.

On a positive note there are many things that L&D departments and their organisations can do to change and adapt, but they must move fast. Adopting Dr Quinn’s performance augmentation mindset, and a range of practices that will support it, is a very good start.

Fascinating post, Charles! Loved the time analogy. As someone who has been involved in learning and development for many years, I've been fortunate to work with colleagues who have taken a mainly facilitative rather than content-based approach. I've always felt what we need is a flipped workplace akin to the flipped classroom. Technology is breaking down the barriers of time and space. Gathering physically is still an essential part of being human. So I see the two co-existing. L&D needs to move further towards facilitating collective sense-making and helping individuals become skilled at using technology for self-help. The challenge is as much about changing mindsets as anything.