L&D departments have been ‘”flipping” for years. In some organisations they are moved from being embedded in HR to reporting into the business line and back again on a regular basis. Some also “flip” between local and global accountability as well.

Most L&D “flipping” is an attempt to ensure a better workforce development service to the organisation.

In fact, there’s no right answer – some L&D departments sit in HR and deliver a great service to the business lines, some don’t. Equally, some L&D departments sitting in the business do a great job and others don’t. There’s no structural silver bullet out there.

ACCOUNTABILITY – THE SILVER BULLET

The silver bullet, however, lies in two accountabilities. Firstly, L&D’s ability to be accountable for business results (or organisational results if you’re in a public sector or not-for-profit organisation). Secondly, there’s an equal need for L&D to be accountable for the efficiency and effectiveness of it’s services. If an L&D department is using sub-optimal approaches, flying ILT trainers around the world to deliver content-heavy classes for example, or is developing expensive media-rich eLearning programmes that only small numbers of employees need to use, it will likely be failing to deliver on these two requirements respectively.

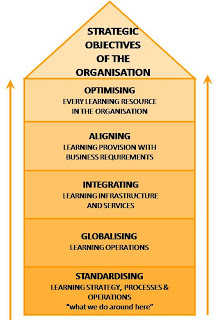

A strategic approach (from both top-down and bottom-up) is needed and get both business accountability and an efficient and effective L&D operation in place. The diagram below is an attempt to break out the high-level parts in these accountabilities. [1] standardising; [2] globalising; [3] integrating; [4] aligning; [5] optimising. Focus on these will result in greater likelihood in L&D being able to deliver a service that brings value to the entire organisation.

ALIGNING L&D WITH ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY

AUTONOMY vs STRATIGIC ALIGNMENT

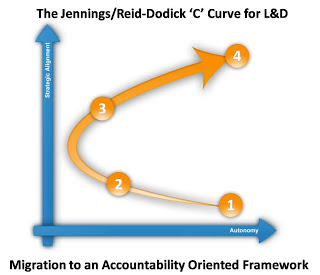

I spent most of my 8 years as CLO at Reuters involved in L&D transformation in one way or another. One tool I found very useful in planning a structure that would work for the organisation was the ‘C’ curve for an accountability-oriented L&D framework. The Global HR Director at Reuters and I developed this ‘C’ curve for L&D to help us make the initial changes.

We used the ‘C’ curve model to define the journey needed to build an L&D function that was accountable for business results, whose operation was closely aligned with the company’s overall strategy, that embedded the ‘efficiency & effectiveness’ mantra but – at the same time – where the component parts of L&D could have some autonomy to operate and make decisions locally.

This ultimately resulted in a federated organisational structure – a small core L&D team sitting in the corporate HR centre managing the overall strategy, alignment, standards, infrastructure etc. while the majority of L&D resources (and their budgets) sat in the various business lines delivering operational L&D services to their stakeholders. L&D was held together by a central governance board (mostly senior business managers, but chaired by the HR Director), and functional reporting lines for each of the Heads of Learning (every major business unit had one) into the CLO (my role).

The ‘C’ curve below shows the steps that were taken to move to an accountability oriented structure that worked for us.

Ideally organisations want to move from [1], where pieces of the L&D puzzle are operating autonomously without being strategically aligned, to [4] where they still have a level of autonomy, but are strategically aligned.

Many organisations are still living with [1] and don’t really know how to move away from having a gaggle of un-coordinated L&D/Training groups who are all doing their own ‘thing’ and often competing internally.

The ‘C curve model is a mechanism for making that move.

It’s highly unlikely that a 1->4 move is achievable without the intermediate [2] and [3] steps. That’s the way found it at Reuters. We first needed to bring all the L&D resources (or as many as we could put our arms around) into the corporate centre’s zone of influence – at [2] – and put the ‘twin pillars’ of standards and infrastructure in place. This meant removing the previous autonomy for the sake of alignment. Then we established a solid governance model [3]. Only then could we return autonomy to the groups by restructuring as a federated service, creating the functional Heads of Learning role and moving most of the L&D people into the various business lines.

The result was a structure that worked for the company. Operational L&D was aligned with the business. Business managers chose how to deploy their L&D resources, how to prioritise their L&D budgets etc. At the same time, corporate HR maintained overview of L&D and ensured that strategy, standards and infrastructure services were consistent across the organisation.

As I said, there’s no structural silver bullet, but this model can be very useful as a means to get both alignment and accountability.

ConsultMember of the Internet Time Alliance and Co-founder of the 70:20:10 Institute, Charles Jennings is a leading thinker and practitioner in learning, development and performance.

ConsultMember of the Internet Time Alliance and Co-founder of the 70:20:10 Institute, Charles Jennings is a leading thinker and practitioner in learning, development and performance.

I particularly like the "C" curve. That is exactly what I have experienced in two large corporate organisations – and they seem to get stuck between 2 & 3 and literally whither on the vine at that point.

Is there a leadership issue here? Do we need a different sort of L&D leader to take a function from 1-2-3 from one who can take it from 2-3-4? The critical evolving issues are likely to be different and the relationships with all of the key stakeholders of all types will change as this evolution takes place.

Also, the shift from 2-3 needs to happen fairly rapidly since the tensions to retract are significant.